So there’s an obituary of Southern Gothic master Wiliam Gay in last week’s daily NY Times (Feb 29th) that I almost missed, which has a few illuminating details and quotes, such as describing his novel Twilight (2006) as “textbook Southern Gothic” (which I think is accurate: It’s not one of his best books but it certainly is true to Southern Gothic genre) and his own feeling of never fitting in, either as construction worker or intellectual writer: “I’ve always felt sort of like in between things,” he said after he had given up his life as a laborer. “Like I fit in when I was working construction. I more or less could do my job. I didn’t get fired. I got paid. I could do it. But it was always sort of like working under cover. Now when I’m meeting academic people and going to these things they have, basically it’s still the same thing. I’m still under cover. Then, I was sort of a closet intellectual passing as a construction worker. Now, I’m a construction worker passing as an academic.”

But it ends with the best quote:

“At his death he was about to turn in a new novel, tentatively titled “The Lost Country.” Aware of the oddity of his late-blooming writing career, he was often reminded of it by the people he lived among. When he began to be published, a woman he knew asked him if anyone was helping him to write his books. “I said, ‘What do you mean by that?’ ” he recalled. “And she said, ‘Well, I knew your family a long time, and they’re not that smart. I knew you when you were younger, and you’re not that smart. I was wondering if you had somebody who took out the little words and put in the big words.’ ”—http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/arts/william-gay-novelist-rooted-in-tennessee-dies-at-70.html?pagewanted=2&ref=books

That’s a sign of quality fiction, when you reach Shakespeare Conspiracy Theory territory, in which someone considers the writing so good that they don’t think such an uneducated, unwashed lout such as you could have written it. I also love that idea of a writer’s job (or perhaps an editor’s) as being one of “taking out the little words and putting in the big words,” though I rather think Ernest Hemingway would differ, such as his famous quote about Faulkner’s writing (and Gay is most definitely a literary son of Faulkner):

“Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

The obit doesn’t mention that The Lost Country was due to be published for a long, long time. I heard through the grapevine that he had been working on this novel for many years, that it was rumored to be his masterpiece, until the manuscript mysteriously disappeared from his home. It was believed to be stolen. I don’t know if it’s true or not: One of the details to back that up is that he wrote in longhand on yellow legal pads, and the novel was a great stack of those. It’s a cool story—How many writers have had their novels stolen? Many of us are lucky to get the books read, much less stolen before they are edited and set in print. Gay must have been doing something right. And I’ve theorized that he simply rewrote it from memory (as I recently did with my novel The Bird Saviors, after I lost the entire first draft to a harddrive crash, with no backup!), and that’s what caused the years-long delay in the publication for The Lost Country. If we’re lucky, maybe a complete manuscript exists, and will be published posthumously by his estate.

A friend (Yo, Morris!) and I did a postmortem on William Gay, especially in relation to Cormac McCarthy, after my comment about his being a “Poor man’s Cormac McCarthy, which is a good thing to be.” He pointed out Gay had moments where he surpassed McCarthy, and I agree, in one particular form of fiction: Gay wrote a handful of short story Classics, without a doubt: “The Paperhanger” is the most obvious there. McCarthy is our great novelist, and he left the short story arena open for Gay.

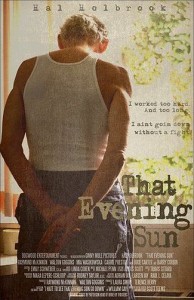

In honor of his passing, I think we should all reread his best fiction, and watch his two films, like this one: