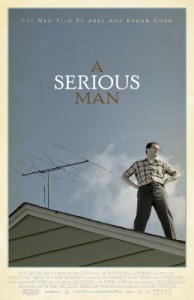

So it’s no secret I’m a serious fan of the Coen Brother’s latest film, A Serious Man, which I’ll call a Little Masterpiece. (Why “little”? It doesn’t have the epic sweep of, say, Doctor Zhivago, but then again, it’s not long and tedious, either. It does have some snowy scenes in Russia, just no Omar Sharif and Julie Christie canoodling in the snowy house.) Judging from the bad reviews it received, it’s also certainly misunderstood by many—though I’ll note it was a finalist for Best Picture. Guest blogger Elizabeth May takes on the critics, and they lose:

Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man Not Taken Seriously Enough

After analyzing The New Yorker’s and The New York Times’ reviews of A Serious Man, for a unit I taught on film reviewing, I was disappointed and disheartened by David Denby’s and A.O. Scott’s analysis or should I say, lack of analysis. David Denby says the film is “in their bleak, black, belittling mode, and it’s hell to sit through” while A.O. Scott reviews the film from a narrow, religious lens, missing universal themes of the human condition. He claims, “When we first meet Larry, in the spring of 1967, his tenure case is pending, his son’s bar mitzvah is approaching, and, a lot of bad stuff is about to happen, for no apparent reason.” I quibble with his judgment that bad stuff happens in the film “for no apparent reason.” The following kibitzes that just as “actions have consequences” in this film, details have reason.

The puzzles the film poses haunt me like the bad mojo that follows Larry Gopnik around in the film, and among friends, colleagues, and students I have been unable to stop jabbering about the details, symbols, and significances in the underrated A Serious Man. Exactly what details I’m disappointed were left out of such high-brow reviews include, the relevancy of the Yiddish-folktale prologue and the metaphysical symbolism of the Mentaculus, the Uncertainty Principle, and Schrodinger’s Paradox on the plot-line of the film.

In comments about the allegorical prologue, both reviewers mention the uncertainty of an authentic dybbuk but don’t offer any explanation of possible answers. And while I wouldn’t dare draw absolute conclusions concerning director-intentions, my students discussed the prologue as a puzzle for the viewer to unravel through the details in the film. With such bad luck showered on Larry, we determined the husband in the prologue was correct in thinking Treitle Groshkover wasn’t a dybbuk and they were in fact “cursed.” This point of view, we argued, isn’t exclusive if you question who is cursed in the film and what is considered bad luck. After all, Sy Abelman is the character who died, and Oy, did he have it coming.

After first viewing A Serious Man, I compared the film to Vladimir Nabokov’s famous short story “Signs and Symbols,” in which literary critics have argued against the details being inconsequential to understanding the ending. By considering the tone of Nabokov’s details, it is argued a reader should understand the relevance “zero” and “crab apple” have on the story’s dark ending. Similarly, I concluded the Brothers Coen wanted their audience to “do the math”; add up the signs and symbols to answer questions concerning the film’s ambiguities, greater meanings and significances.

Furthermore, the mathematical theorems in the film were the clues by which my students deduced the meaning of certain character decisions. For example, when Larry explains the uncertainty principle to his students in a dream, he says even though nothing can be explained, they will be held accountable for it on their exam. The principle holds for Larry as well. Even though he can’t explain the circumstances of his life or find answers to what it all means, the film articulates specific ways in which he is held accountable for his decisions and actions or inaction. The most glaring example being the moment when he changes Clive’s grade to a passing grade and then suffers the consequences of an ill-fated phone call. Other examples include the ease with which he is taken advantage of by his kids, wife, brother, and Sy Abelman.

While some viewers were disappointed with the “open ending,” we argued there might be clues and metaphors to explain the possibilities. Firstly, we felt the philosophy of the Uncertainty Principle, was metaphorical of the question whether or not the tornado would hit and that the ending could be justified in this light. However, if you viewed the ending from a signs-and-symbols approach and considered that “actions have consequences” the editing of the film’s conclusion, switching from Larry changing Clive’s grade to David deciding whether or not to pay off his pot debt, seems to imply a correlation between their actions or inaction. Directly after Larry gives Clive a passing grade, he receives an unlucky phone call from his doctor delivering what is ambiguous but obviously, bad news. If we are supposed to parallel this action and consequence with David hesitating to give the twenty bucks to Mike Fagle, we might conclude if he doesn’t pay the money he’ll suffer the consequences of the tornado.

One student argued the film was about kharma and I enjoyed this term being applied to a film dealing with Jewish culture. Students understood a certain give and take, yen and yang, good and evil struggle for balance running through the film. Uncle Arthur’s Mentaculus symbolized this balance when considering it’s relationship to Schrodinger’s Paradox and the Uncertainty Principle. The Mentaculus extrapolates probability theorems while Schrodinger’s Paradox and the Uncertainty Principle are ambiguous. Furthermore this represents a paradox of characterization between Larry and his brother Arthur. While Larry is focused on uncertainty; Larry is focused on probable answers. As if one holds the answer for the other and if only they could combine their brains, they might solve the riddles of their lives.

Furthermore, themes and refrains in the dialogue such as, “I didn’t do anything” correlate with specific moments in the film. When Larry Gopnik declares to Clive, “In this office, actions have consequences,” the lesson applies to Larry as well. Interpreting the ways in which Larry’s character is taken advantage of throughout the rest of the film suggests that even inaction—not doing anything—results in “consequences,” such as being taken advantage of by characters like Sy Abelman.

In the end, I believe Rabbi Scott embodies the right perspective in this bit of wisdom he offers to Larry, “Look at the parking lot, Larry.” I’ve adopted these words as my new mantra and the possibility lurking in that gray concrete expanse conveys worlds to me. “Just look at that parking lot.”

- October 2023

- September 2023

- September 2021

- April 2020

- September 2019

- May 2019

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- December 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

Recent Posts

- Aliens Among Us: Probing Hillbillies and Freaking Shut-ins, How Netflix’s “Encounters” and Hulu’s “No One Will Save You” Prep Us for the Coming Alien Apocalypse, Kind of

- My Life as a Bob Odenkirk Character: On How Watching Netflix’s Black Mirror episode “Joan Is Awful” Mimicked My Experience of Watching the AMC series Lucky Hank

- “Bobcats, Bobcats, Bobcats”: Animal Life and a Tribute to “Modern Family”

- “The North Water”: This Ain’t Your Daddy’s Moby Dick

- Day 25: On David Quammen's "Spillover": Terrific Book That Foretold Our Pandemic, Kind of

Recent Comments

No comments to show.