So a year ago, on August 24th-25th, Hurricane Harvey crashed into the Texas coast, roughly equaling, in monetary damage, the destruction of Hurricane Katrina back in 2005. Based on my novel Goodnight, Texas, you could say I predicted it: I imagined and wrote about a similar storm hitting the Texas coast, and how it would affect the people, all busy with the personal squabbles of a resort town slash fishing village in a time of dramatic climate change. It describes a world of seafood cafes and shrimp boats, suntan lotion and salt spray, enveloped by the charm of the sunny, windy Gulf. And for all of William Faulkner’s famous concern with the past, in the 21stcentury I think this is now what novelists often do: Imagine a future to understand the present.

Although I’ll attest to not having a prophetic bone in my body, I do obsess on what might happen in the coming years—where we’re headed, what dangers lurk in the near-at-hand. Storms are on the horizon, as usual: My family originally hails from Galveston, and some of my ancestors perished in the epic Storm of 1900, which is best described in Erik Larson’s Isaac’s Storm (1999). I’ve weathered several hurricanes: Carla frightened us in my earliest childhood years and Alicia struck my parents’ home in the 1980s, flooding the first floor of my parents’ home with four feet of water. In the early 2000s I got the idea to set a novel in a coastal town that gets hit by a powerful hurricane, disrupting the characters’ lives and showing how life-changing events happen when you’re not looking. When Hurricane Harvey arrived last year it made landfall at Copano Bay and the tiny community of Holiday Beach, where I once lived—a sun-bleached neighborhood of houses on stilts, where we would sneak into the community swimming pool to cool off in the warm Texas nights.

While Nostradamus is known for his poetic prophecies, I think of myself as more of a futurist, in the great tradition of others such as sci-fi masters like Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke to H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, and even Cormac McCarthy, whose apocalyptic The Road (2006), with its cannibals and blasted landscape, we all hope never comes to pass. The method of Eugene Linden’s nonfiction The Future in Plain Sight (1998) is right up my alley: Pay attention to the world and try to guess where things are going. You’ll be wrong some of the time (ask the Peak Oil doomsayers, for one) and probably right some of the time. I’m now a fan of the BBC/Netflix program “Black Mirror,” which does exactly that. Watch the “Nosedive” episode from Season 3 and consider how close we are to this mix of smartphone and surveys/ratings dominance morphing to a world turned upside-down.

On a recent morning in my home in southern Colorado, I stepped out on the balcony to check the fire smoke. In this 21stcentury climate-changed world, it’s a daily ritual. Especially in June, which tends to be our hottest, driest month. About 50 miles south of us raged the Spring Fire, near Fort Garland, Colorado, at over 40,000 acres. For days my eyes burned, my sinuses stung with the smell of burnt trees, and we all suffered a lingering dread of where the fire might turn.

Now my new novel, The Donkey Woman & the Invisible World, features a plotline that involves a horrific fire descending upon a Colorado town. I see it less as predicting the future than keeping my eyes open.

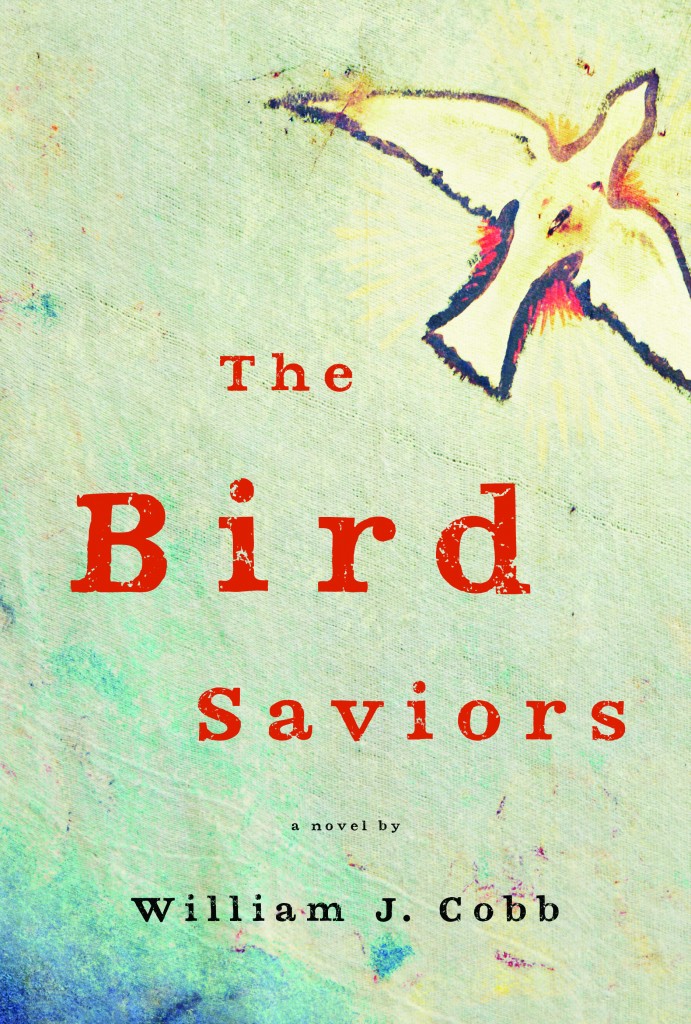

One of the scariest books I’ve read in the last year was not a horror novel, but Michael Kodas’s nonfiction Megafire: The Race to Extinguish a Deadly Epidemic of Flame (2017). It describes people like myself, with hideaway homes in the mountains, being unaware of how fast fires can rush upon them, especially when driven by wind. One of the things novelists do is imagine what awful things could happen and disrupt the gentle or chaotic flow of our ordinary lives, as a way to confront both our fears of what’s to come and our love for what we have. But one thing that Goodnight, Texas and my last novel, The Bird Saviors, do not forget: “This too shall pass.” Life goes on. The Texas coast is bouncing back from the devastation of Hurricane Harvey. Yes, I’m afraid of megafires and losing my home. And I have to admit that during drought years, like this one, it often feels as if it will never rain again. But here’s a prediction: It will.