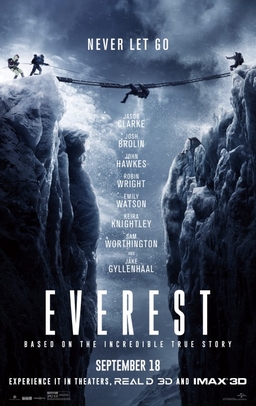

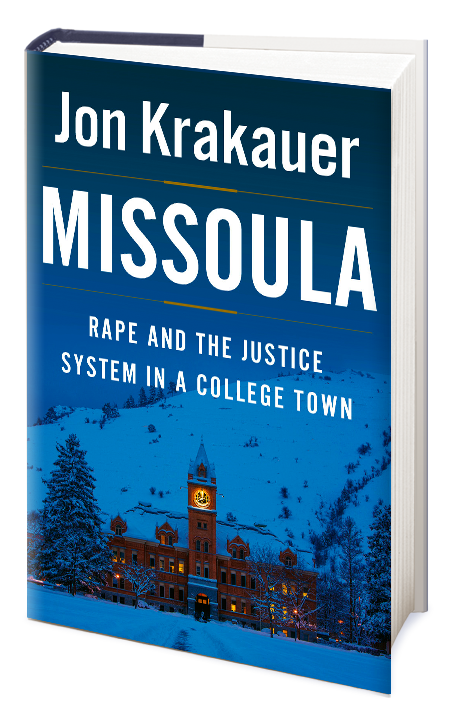

So last weekend I happened to see the new film Everest, which recapitulates many of the events in Jon Krakauer’s bestseller Into Thin Air (1997), about the disastrous year when 11 climbers died on Mount Everest, circa 1996—which has since been eclipsed by even greater death tolls, such as this year’s avalanche that killed 22 people—and earlier in the summer I read Krakauer’s new book of nonfiction, Missoula: Rape the Justice System in a College Town, and the two provide a nice contrast of cultural moments/trends.

To begin with, Everest seems dated and clunky. It’s sad and touching at times—detailing the final agonizing moments of Rob Hall, for instance—but it all seems to be rehashing the past, and not in the way that sheds new light on that particular moment in time with great import for ours, but almost as if this were a new story, which it isn’t. The best images are the sweeping visuals of Everest itself and the snaking line of climbers ascending the steep white slopes, while the worst visual moments are the close-up action sequences which you can tell are being filmed on a set, with the actors all too fresh-faced for the grueling conditions they are supposed to be enduring. Actually the actors do a terrific job, with Jason Clarke as the commercial guide Rob Hall, and House of Cards henchman Michael Kelly as Krakauer himself, who comes across as a minor player in the saga. But by the end of the film I somewhat regretted even bothering to go see it. It’s certainly a well-done reenactment of sorts, but it seemed to be lacking a fresh perspective. Krakauer conveyed the tragedy in much greater detail and understanding, and while he tends to moralize a bit too much for my tastes, he does make a convincing argument of what went wrong on Everst that year: Too many climbers made the conditions too treacherous, many of them weren’t qualified, and the rise of commercial guide services contributed to the dangerous conditions and the disaster.

It’s to Krakauer’s credit that he’s moved on from that particular soapbox, which is essentially now two decades old, and in the meantime has written about such disparate topics as Pat Tillman’s death by “friendly fire” in Where Men Win Glory (2009), Greg Mortensen’s dubious humanitarian ventures in Three Cups of Deceit (2011), and, for my money, Krakauer’s best book, Under the Banner of Heaven (2003), about a murderous family of unhinged polygamists.

This year’s book is Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town, which I read both out of affection for Krakauer’s work and natural curiosity, as I (partly) live in a college town—State College, Pennsylvania, home of Penn State University, a school that has been rocked by its own sex scandals and tangled tales of justice involving the football team and its coaches.

Before I read it, I wondered why I hadn’t heard much about Missoula. After I finished it, I knew why. It’s not a bad book, but it’s certainly not an enjoyable read. It essentially details several date-rape cases that occurred in Missoula, Montana in the last decade, cases that often involve football players, including the star quarterback, and the events overlap so much that Krakauer makes a compelling case for the importance of this in our moment in time. His dry, thorough description of the events and ramifications is a contrast to last year’s now-discredited Rolling Stone article about alleged fraternity rapes at the University of Virginia. Although Krakauer comes across as too eager to blame some of the actors in these real-life dramas, ultimately he seems to do a good job: I have to add the “seems to” because obviously I don’t really know all the details, and am simply reading one person’s version of the events, which are greatly disputed by the various parties involved. And that’s where I have to say the book is both good, and somewhat sordid. Krakauer presents all the gritty details, and it made me feel sorry for all of the students involved, both female victims and male perpetrators. If you wanted to point to one culprit, alcohol seems to be the deciding factor in most of the stories. If they weren’t drunk, they probably wouldn’t do these awful things. When I finished the book, I was glad to be done with it. And as I have a daughter who will most likely be on a college campus in a similar world, it all resonates with me. I imagine most parents hope their children can avoid these horrible situations, and do our best to teach them that socializing doesn’t have to include getting wasted and hurting yourself or anyone else. Part of me hopes that we don’t hear this same sordid story in the next decade, when my daughter will be in college. But of course by then all the university students will be taking classes on-line, secure in their own rooms, wearing pajamas and safe and isolated as they can be.

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- November 2025

- October 2023

- September 2023

- September 2021

- April 2020

- September 2019

- May 2019

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- December 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

Recent Posts

- On Tom Waits in “Father Mother Sister Brother”: Grifter Like Me

- On “After the Hunt” and “The Tavern at the End of the World”: Land of the Lost Professors

- On Morris Collins’s Novel “The Tavern at the End of History” (2026) and the Coen Brothers’ Film “A Serious Man” (2009)

- “Song Sung Blue” Makes Kate Hudson Oscar Worthy

- On Randall K. Wilson’s “A Place Called Yellowstone”: Award-Winning History of Yellowstone National Park

Recent Comments

No comments to show.